Campus orientation tours, backpacks filled with shiny new binders, freshly minted course syllabi: For students, a new school year is a time of optimism, excitement and new experiences. Unfortunately, it can also be a time of increased risky alcohol behavior, especially for first-year students. Freedom from parental supervision, socializing with peers who can legally purchase alcohol and age-appropriate impulses to experiment make the first year of college a time when alcohol consumption increases significantly for many. Nguyen et al. (2011) found that first-years’ estimated blood alcohol content (BAC) rose sharply, starting as soon as they arrived on campus.

The good news is that many first-year students already have healthy behaviors around alcohol, and social norms marketing may be very useful for changing the perceptions of those with less healthy behaviors. U.S. studies have consistently found that more than a third of first-year students do not drink alcohol at all, or drink only lightly (Pederson et al., 2010; Boekeloo et al., 2009; Fromme et al., 2008). Pederson et al. studied the perception versus reality of college drinking, and found that first-year students perceived other first-years drinking over 16 drinks per week, while in reality this group reported fewer than 8 drinks weekly. Older class-years had similar misperceptions. Boekeloo et al. reported that residence hall neighbors are an important peer group for first-year students, and that social norms programs can impact drinking behavior in residence halls, but also may reduce “secondhand” negative effects on non-drinkers in the residence hall.

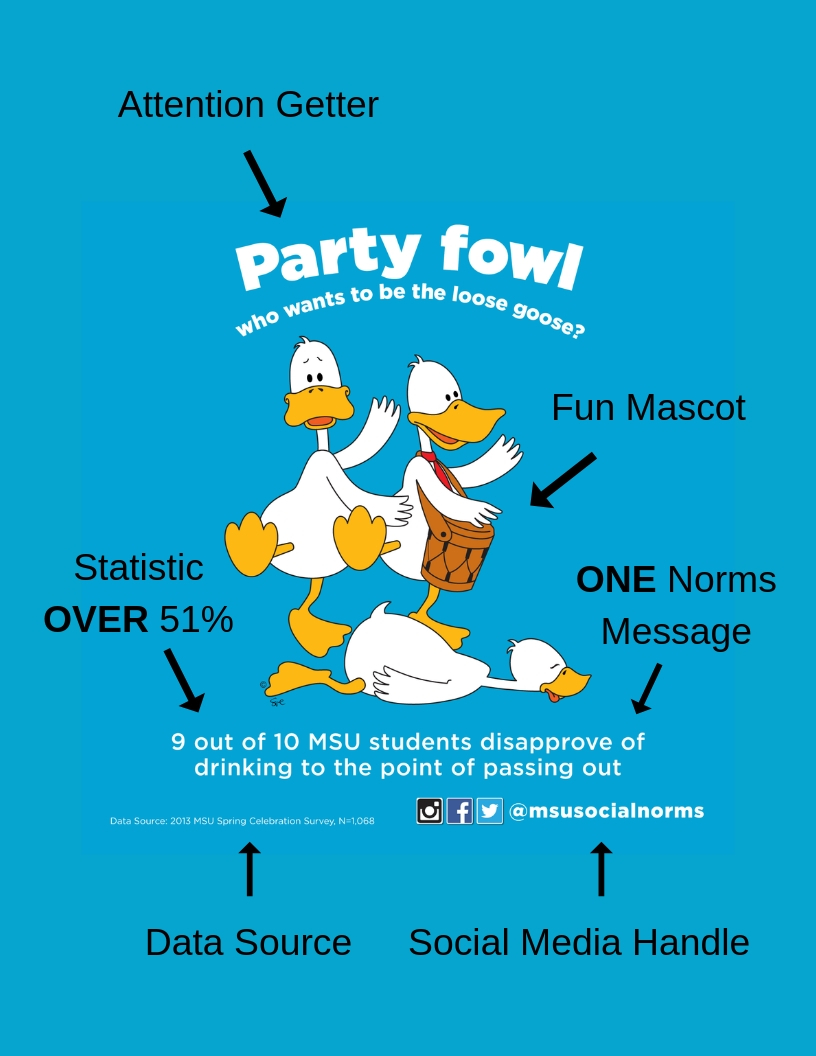

Of course, we hope that our website will provide you with ideas and helpful tools for initiating or improving a Social Norms campaign to address risky drinking – your first campaign materials should already be distributed, or be ready for distribution, at the beginning of the school year. Nonetheless, although Social Norms interventions have proven their effectiveness in correcting misperceptions, decreasing drinking and decreasing negative consequences of drinking, a comprehensive prevention plan will include more than social norms interventions.

Borsari et al. (2007) provide us with some additional examples of how colleges can modify aspects of the environment to support non-drinking:

- Make alcohol harder for underage students to obtain. Campus policies should be clearly communicated and consistently enforced. Colleges should work with off-campus bars and stores to ensure employees are trained on deterring underage drinkers, and should seek sanctions against establishments that are lax about drinking age and other laws. Colleges should work with localities and other regulators to establish policies that increase the price of alcohol and reduce the venues and hours when alcohol is sold.

- Provide a variety of evening and weekend alcohol-free programs, such as movies, coffeehouses, recreational sports, and other group activities. Keep student centers and fitness centers open late on weekend evenings. Remember that Thursday is also a significant drinking time.

- Target these activities particularly to college men, who are more likely than women to use alcohol while socializing.

- Residence hall advisors (RA’s) have very important roles in providing first-year students with guidance and promoting responsible behavior. RA’s should receive specialized training on reducing risky drinking behaviors, and staffing halls with older students or adult professionals can be especially effective at establishing healthy cultures within residence halls.

- Increase volunteer and service learning opportunities at the beginning of the semester. These structured activities can substitute for unstructured time, foster new interests, and provide enjoyable and rewarding ways to feel connected to the larger world. Students who volunteer are less likely to binge drink.

- Increase academic demands at the beginning of the semester. Students drink less when they have less free time, such as during exam weeks.

- Modify classes to reduce students’ unstructured time: Increase incentives to attend class such as pop quizzes and penalties for absences; schedule classes in the morning, especially Friday morning (this is shown to reduce alcohol consumption the night before).

- Teach time management skills to students, so they learn to use unstructured time more effectively.

We know how overwhelming the demands of a new school year can be, but it can also be a good time for evaluating (at least informally) your school’s prevention environment: Are prevention efforts comprehensive? A bit tired and well-worn? Isolated or integrated? And, of course, do they include social norms interventions based on best practices?

References

(Also see our Literature page for additional resources, including first-year students and other college events associated with increased alcohol consumption)

Boekeloo, B. O., Bush, E. N., & Novik, M. G. (2009). Perceptions about residence hall wingmates and alcohol-related secondhand effects among college freshmen. Journal of American College Health, 57(6), 619-628.

Borsari, B., Murphy, J. G., & Barnett, N. P. (2007). Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addictive behaviors, 32(10), 2062-2086.

Fromme, K., Corbin, W. R., & Kruse, M. I. (2008). Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental psychology, 44(5), 1497.

Nguyen, N., Walters, S. T., Wyatt, T. M., & DeJong, W. (2011). Use and correlates of protective drinking behaviors during the transition to college: Analysis of a national sample. Addictive behaviors, 36(10), 1008-1014.

Pedersen, E. R., Neighbors, C., & LaBrie, J. W. (2010). College students’ perceptions of class year-specific drinking norms. Addictive behaviors, 35(3), 290-293.